|

November 1, 2007

Paul

Tibbets Interview

Courtesy Aviation Publishing Group

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

We're seated here, two old gaffers. Me and

Paul Tibbets, 89 years old, brigadier-general retired, in his

home town of

Columbus

,

Ohio

, where he has lived for many years.

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

Hey, you've got to correct that. I'm only 87.

You said 89.

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

I know. See, I'm 90. So I got you beat by

three years.

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

Now we've had a nice lunch, you and I and your

companion. I noticed as we sat in that restaurant, people

passed by. They didn't know who you were. But once upon a

time, you flew a plane called the Enola Gay over the city of

Hiroshima, in Japan, on a Sunday morning - August 6 1945 - and a bomb fell. It

was the atomic bomb, the first ever. And that particular

moment changed the whole world around. You were the pilot of

that plane.

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

Yes, I was the pilot.

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

And the Enola Gay was named after...

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

My mother. She was Enola Gay Haggard before

she married my dad, and my dad never supported me with the

flying - he hated airplanes and motorcycles. When I told them

I was going to leave college and go fly planes in the Army Air

Corps, my dad said, "Well, I've sent you through school,

bought you automobiles, given you money to run around with the

girls, but from here on, you're on your own. If you want to go

kill yourself, go ahead, I don't give a damn." Then Mom

just quietly said, "Paul, if you want to go fly

airplanes, you're going to be all right." And that was

that.

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

Where was that?

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

Well, that was

Miami, Florida

. My dad had been in the real estate business down there for

years, and at that time he was retired. And I was going to

school at

Gainesville,

Florida, but I had to leave after two years and go to

Cincinnati

because Florida

had no medical school.

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

You were thinking of being a doctor?

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

I didn't think that, my father thought it. He

said, "You're going to be a doctor," and I just

nodded my head and that was it. And I started out that way;

but about a year before I was able to get into an airplane,

fly it - I soloed - and I knew then that I had to go fly

airplanes.

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

Now by 1944 you were a pilot - a test pilot on

the program to develop the B-29 bomber. When did you get word

that you had a special assignment?

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

One day [in September 1944] I'm running a test

on a B-29, I land, a man meets me. He says he just got a call

from General Uzal Ent [commander of the 2nc Air Force] at

Colorado Springs, he wants me in his office the next morning at nine o'clock.

He said, "Bring your clothing - your B4 bag - because

you're not coming back". Well, I didn't know what it was

and didn't pay any attention to it - it was just another

assignment. I got to

Colorado Springs

the next morning perfectly on time. A man named Lansdale

met me, walked me to General Ent's office and closed the door

behind me. With him was a man wearing a blue suit, a US Navy

captain - that was William Parsons, who flew with me to

Hiroshima

- and Dr. Norman Ramsey,

Columbia

University

professor in nuclear physics. And

Norman

said: "OK, we've got what we call the Manhattan Project.

What we're doing is trying to develop an atomic bomb. We've

gotten to the point now where we can't go much further till we

have airplanes to work with." He gave me an explanation

which probably lasted 45, 50 minutes, and they left. General

Ent looked at me and said, "The other day, General Arnold

[Commanding General of the Army Air Corps] offered me three

names. "Both of the others were full colonels; I was a Lieutenant

Colonel. He said that when General Arnold asked

which of them could do this atomic weapons deal, he replied

without hesitation, "Paul Tibbets is the man to do

it." I said, "Well, thank you , sir."

Then he

laid out what was going on and it was up to me now to put

together an organization and train them to drop atomic weapons

on both Europe and the Pacific -

Tokyo

.

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

Interesting that they would have dropped it on

Europe

as well. We didn't know that.

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

My edict was as clear as could be. Drop

simultaneously in

Europe

and the Pacific because of the secrecy problem - you couldn't

drop it in one part of the world without dropping it in the

other. And so he said, "I don't know what to tell you,

but I know you happen to have B-29's to start with. I've got a

squadron in training in Nebraska

- they have the best record so far of anybody we've got.

I

want you to go visit them, look at them, talk to them, do

whatever you want. If they don't suit you, we'll get you some

more." He said: "There's nobody who could tell you what

you have to do because nobody knows. If we can do anything to

help you, ask me." I said thank you very much.

He said,

"Paul, be careful how you treat this responsibility,

because if you're successful you'll probably be called a hero.

And if you're unsuccessful, you might wind up in prison."

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

Did you know the power of an atomic bomb? Were

you told about that?

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

No, I didn't know anything at that time. But I

knew how to put an organization together. He said, "Go

take a look at the bases, and call me back and tell me which

one you want." I wanted to get back to Grand Island,

Nebraska; that's where my wife and two kids were, where my laundry was

done, and all that stuff. But I thought, "Well, I'll go

to Wendover [Army Airfiedl, in Utah] first and see what they've got."

As I came in over the

hills I saw it was a beautiful spot. It had been a final

staging place for units that were going through combat crew

training, and the guys ahead of me were the last P-47 fighter

outfit. This Lieutenant Colonel in charge said, "We've

just been advised to stop here and I don't know what you want

to do...but if it has anything to do with this base, it's the

most perfect base I've ever been on. You've got full machine

shops, everybody's qualified, they know what they want to do.

It's a good place."

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

And now you chose your own crew.

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

Well, I had mentally done it before that. I

knew right away I was going to get Tom Ferebee [the Enola Gay's

bombardier] and Theodore "Dutch" van Kirk

[navigator] and Wyatt Duzenbury [flight engineer].

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

Guys you had flown with in

Europe

?

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

Yeah.

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

And now you're training. And you're also

talking to physicists like Robert Oppenheimer [senior

scientist on the

Manhattan

project].

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

I think I went to Los Alamos [the

Manhattan

project HQ] three times, and each time I got to see Dr.

Oppenheimer working in his own environment. Later, thinking

about it, here's a young man, a brilliant person. And he's a

chain smoker and he drinks cocktails. And he hates fat men.

And General Leslie Groves [the general in charge of the Manhattan

project], he's a fat man, and he hates people who smoke and

drink. The two of them are the first, original odd couple.

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

They had a feud, Groves

and Oppenheimer?

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

Yeah, but neither one of them showed it.

Each

one of them had a job to do.

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

Did Oppenheimer tell you about the destructive

nature of the bomb?

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

No.

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

How did you know about that?

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

From Dr Ramsey. He said the only thing we can

tell you about it is, it's going to explode with the force of

20,000 tons of TNT. I'd never seen 1 lb of TNT blow up. I'd

never heard of anybody who'd seen 100 lbs of TNT blow up. All

I felt was that this was gonna be one hell of a big bang.

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

Twenty thousand tons - that's equivalent to

how many planes full of bombs?

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

Well, I think the two bombs that we used [at

Hiroshima

and

Nagasaki

] had more power than all the bombs the Air Force had used

during the war in

Europe

.

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

So Ramsey told you about the possibilities.

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

Even though it was still theory, whatever

those guys told me, that's what happened. So I was ready to

say I wanted to go to war, but I wanted to ask Oppenheimer how

to get away from the bomb after we dropped it. I told him that

when we had dropped bombs in Europe and

North Africa

, we'd flown straight ahead after dropping them - which is

also the trajectory of the bomb. But what should we do this

time? He said, "You can't fly straight ahead because

you'd be right over the top when it blows up and nobody would

ever know you were there." He said I had to turn tangent

to the expanding shock wave. I said, "Well, I've had some

trigonometry, some physics. What is tangency in this

case?" He said it was 159 degrees in either direction.

"Turn 159 degrees as fast as you can and you'll be able

to put yourself the greatest distance from where the bomb

exploded."

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

How many seconds did you have to make that

turn?

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

I had dropped enough practice bombs to realize

that the charges would blow around 1,500 ft in the air, so I

would have 40 to 42 seconds to turn 159 degrees. I went back

to Wendover as quick as I could and took the airplane up. I

got myself to 25,000 ft and I practiced turning, steeper,

steeper, steeper and I got it where I could pull it round in

40 seconds. The tail was shaking dramatically and I was afraid

of it breaking off, but I didn't quit. That was my goal. And I

practiced and practiced until, without even thinking about it,

I could do it in between 40 and 42, all the time. So, when

that day came....

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

You got the go-ahead on August 5.

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

Yeah. We were in Tinian [the US

island base in the Pacific] at the time we got the OK. They

had sent this Norwegian to the weather station out on Guam

[the

US's westernmost territory] and I had a copy of his report. We

said that, based on his forecast, the sixth day of August

would be the best day that we could get over Honshu [the

island on which

Hiroshima

stands]. So we did everything that had to be done to get the

crews ready to go: airplane loaded, crews briefed, all of the

things checked that you have to check before you can fly over

enemy territory. General Groves had a brigadier general who

was connected back to

Washington

DC

by a special teletype machine. He stayed close to that thing

all the time, notifying people back there, all by code, that

we were preparing these airplanes to go any time me after

midnight on the sixth. And that's the way it worked out. We

were ready to go at about four o'clock in the afternoon on the

fifth and we got word from the President that we were free to

go: "Use me as you wish." They give you a time

you're supposed to drop your bomb on target and that was 9:15

in the morning , but that was Tinian

time, one hour later than Japanese time. I told Dutch,

"You figure it out what time we have to start after

midnight to be over the target at 9 a.m."

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

That'd be Sunday morning.

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

Well, we got going down the runway at right

about 2:15 a.m. and we took off, we met our rendezvous guys,

we made our flight up to what we call the initial point, that

would be a geographic position that you could not mistake.

Well, of course we had the best one in the world with the

rivers and bridges and that big shrine. There was no mistaking

what it was.

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

So you had to have the right navigator to get

it on the button.

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

The airplane has a bomb sight connected to the

autopilot and the bombardier puts figures in there for where

he wants to be when he drops the weapon, and that's

transmitted to the airplane. We always took into account what

would happen if we had a failure and the bomb bay doors didn't

open; we had a manual release put in each airplane so it was

right down by the bombardier and he could pull on that. And

the guys in the airplanes that followed us to drop the

instruments needed to know when it was going to go. We were

told not to use the radio, but, hell, I had to. I told them I

would say, "One minute out," "Thirty seconds

out," "Twenty seconds" and "Ten" and

then I'd count, "Nine, eight, seven, six, five, four

seconds", which would give them a time to drop their

cargo. They knew what was going on because they knew where we

were. And that's exactly the way it worked; it was absolutely

perfect. After we got the airplanes in formation I crawled

into the tunnel and went back to tell the men, I said,

"You know what we're doing today?" They said,

"Well, yeah, we're going on a bombing mission." I

said, "Yeah, we're going on a bombing mission, but it's a

little bit special." My tail gunner, Bob Caron, was

pretty alert. He said, "Colonel, we wouldn't be playing

with atoms today, would we?" I said, "Bob, you've

got it just exactly right." So I went back up in the

front end and I told the navigator, bombardier, flight

engineer, in turn. I said, "OK, this is an atom bomb

we're dropping." They listened intently but I didn't see

any change in their faces or anything else. Those guys were no

idiots. We'd been fiddling round with the most peculiar-shaped

things we'd ever seen. So we're coming down. We get to that

point where I say "one second" and by the time I'd

got that second out of my mouth the airplane had lurched,

because 10,000 lbs had come out of the front. I'm in this turn

now, tight as I can get it, that helps me hold my altitude and

helps me hold my airspeed and everything else all the way

round. When I level out, the nose is a little bit high and as

I look up there the whole sky is lit up in the prettiest blues

and pinks I've ever seen in my life. It was just great. I tell

people I tasted it. "Well," they say, "what do

you mean?" When I was a child, if you had a cavity in

your tooth the dentist put some mixture of some cotton or

whatever it was and lead into your teeth and pounded them in

with a hammer. I learned that if I had a spoon of ice cream and

touched one of those teeth I got this electrolysis and I got

the taste of lead out of it. And I knew right away what it

was. OK, we're all going. We had been briefed to stay off the

radios: "Don't say a damn word, what we do is we make

this turn, we're going to get out of here as fast as we

can." I want to get out over the sea of Japan because I

know they can't find me over there. With that done we're home

free. Then Tom Ferebee has to fill out his bombardier's report

and Dutch, the navigator, has to fill out a log. Tom is

working on his log and says, "Dutch, what time were we

over the target?" And Dutch says, "Nine-fifteen plus

15 seconds." Ferebee says: "What lousy navigating.

Fifteen seconds off!"

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

Did you hear an explosion?

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

Oh yeah. The shockwave was coming up at us

after we turned. And the tail gunner said, "Here it

comes." About the time he said that, we got this kick in

the ass. I had accelerometers installed in all airplanes to

record the magnitude of the bomb. It hit us with two and a

half G. Next day, when we got figures from the scientists on

what they had learned from all the things, they said,

"When that bomb exploded, your airplane was 10 and half

miles away from it."

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

Did you see that mushroom cloud?

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

You see all kinds of mushroom clouds, but they

were made with different types of bombs. The Hiroshima

bomb did not make a mushroom. It was what I call a stringer.

It just came up. It was black as hell and it had light and

colors and white in it and grey color in it and the top was

like a folded-up Christmas tree.

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

Do you have any idea what happened down below?

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

Pandemonium! I think it's best stated by one

of the historians, who said: "In one micro-second, the

city of

Hiroshima

didn't exist."

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

You came back and you visited President

Truman.

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

We're talking 1948 now. I'm back in the

Pentagon and I get notice from the Chief of Staff, Carl

Spaatz, the first Chief of Staff of the Air Force. When we got

to General Spaatz's office, General Doolittle was there and a

colonel named Dave Shillen. Spaatz said, "Gentlemen, I

just got word from the President he wants us to go over to his

office immediately." On the way over, Doolittle and

Spaatz were doing some talking; I wasn't saying very much.

When we got out of the car we were escorted right quick to the

Oval Office. There was a black man there who always took care

of Truman's needs and he said, "General Spaatz, will you

please be facing the desk?" And now, facing the desk,

Spaatz is on the right, Doolittle and Shillen. Of course,

militarily speaking, that's the correct order, because Spaatz

is senior, Doolittle has to sit to his left. Then I was taken

by this man and put in the chair that was right beside the

President's desk, beside his left hand. Anyway, we got a cup

of coffee and we got most of it consumed when Truman walked in

and everybody stood on their feet. He said, "Sit down,

please," and he had a big smile on his face and he said,

"General Spaatz, I want to congratulate you on being first

Chief of the Air Force," because it was no longer the Air

Corps. Spaatz said, "Thank you, sir, it's a great honor

and I appreciate it." And he said to Doolittle:

"That was a magnificent thing you pulled flying off of

that carrier," and Doolittle said, "All in a day's

work, Mr. President." And he looked at Dave Shillen and

said, "Colonel Shillen, I want to congratulate you on

having the foresight to recognize the potential in aerial

refueling. We're gonna need it bad some day." And he

said, "Thank you very much." Then he looked at me

for 10 seconds and he didn't say anything. And when he finally

did, he said, "What do you think?" I said, "Mr.

President, I think I did what I was told." He slapped his

hand on the table and said: "You're damn right you did,

and I'm the guy who sent you. If anybody gives you a hard time

about it, refer them to me."

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

Anybody ever give you a hard time?

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

Nobody gave me a hard time.

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

Do you ever have any second thoughts about the

bomb?

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

Second thoughts? No. Studs, look. Number one,

I got into the Air Corps to defend the

United States

to the best of my ability. That's what I believe in and that's

what I work for. Number two, I'd had so much experience with

airplanes. I'd had jobs where there was no particular

direction about how you do it and then of course I put this

thing together with my own thoughts on how it should be

because when I got the directive I was to be self-supporting at

all times. On the way to the target I was thinking: I can't

think of any mistakes I've made. Maybe I did make a mistake:

maybe I was too damned assured. At 29 years of age I was so

shot in the ass with confidence I didn't think there was

anything I couldn't do. Of course, that applied to airplanes

and people. So, no, I had no problem with it. I knew we did

the right thing because when I knew we'd be doing that I

thought, yes, we're going to kill a lot of people, but by God

we're going to save a lot of lives. We won't have to invade [Japan].

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

Why did they drop the second one, the Bock's

Car

[bomb] on

Nagasaki

?

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

Unknown to anybody else - I knew it, but

nobody else knew - there was a third one. See, the first bomb

went off and they didn't hear anything out of the Japanese for

two or three days. The second bomb was dropped and again they

were silent for another couple of days. Then I got a phone call

from General Curtis LeMay [Chief of Staff of the Strategic Air

Forces in the Pacific]. He said, "You got another one of

those damn things?" I said, "Yes sir." He said,

"Where is it?" I said, "Over in Utah."

He said, "Get it out here. You and your crew are

going to fly it." I said, "Yes sir." I sent

word back and the crew loaded it on an airplane and we headed

back to bring it right on out to Tinian and when they got it

to

California debarkation point, the war was over.

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

What did General LeMay have in mind with the

third one?

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

Nobody knows.

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

One big question. Since September 11, what are

your thoughts? People talk about nukes, the hydrogen bomb.

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

Let's put it this way. I don't know any more

about these terrorists than you do; I know nothing. When they

bombed the Trade Centre I couldn't believe what was going on.

We've fought many enemies at different times. But we knew who

they were and where they were. These people, we don't know who

they are or where they are. That's the point that bothers me.

Because they're gonna strike again, I'll put money on it. And

it's going to be damned dramatic. But they're gonna do it in

their own sweet time. We've got to get into a position where

we can kill the bastards. None of this business of taking them

to court, the hell with that. I wouldn't waste five seconds on

them.

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

What about the bomb? Einstein said the world

has changed since the atom was split.

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

That's right. It has changed.

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

And Oppenheimer knew that.

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

Oppenheimer is dead. He did something for the

world and people don't understand. And it is a free world.

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

One last thing, when you hear people say,

"Let's nuke 'em," "Let's nuke these

people," what do you think?

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

Oh, I wouldn't hesitate if I had the choice.

I'd wipe 'em out. You're gonna kill innocent people at the

same time, but we've never fought a damn war anywhere in the

world where they didn't kill innocent people. If the

newspapers would just cut out the shit: "You've killed so

many civilians." That's their tough luck for being there.

|

|

Studs

Terkel:

|

By the way, I forgot to say Enola Gay was

originally called "Number 82." How did your mother

feel about having her name on it?

|

|

Paul

Tibbets:

|

Well, I can only tell you what my dad

said. My mother never changed her expression very much about

anything, whether it was serious or light, but when she'd get

tickled, her stomach would jiggle. My dad said to me that when

the telephone in

Miami

rang, my mother was quiet first. Then, when it was announced

on the radio, he said: "You should have seen the old

gal's belly jiggle on that one."

|

|

to

|

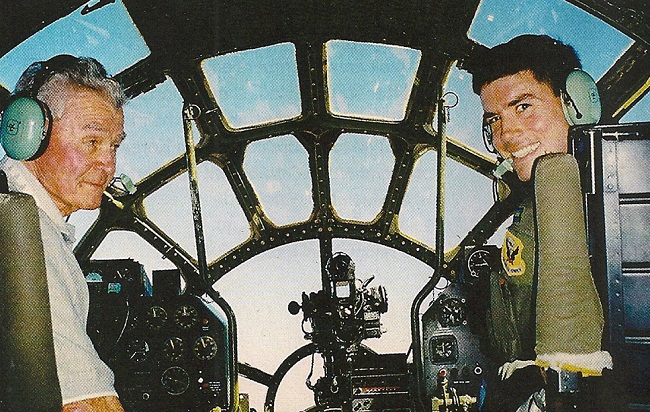

FAST FORWARD TO 1998: BG Paul Tibbetts, Jr in the cockpit with

his grandson, BG Paul Tibbets, IV. They are pictured in the

world's only operational B-29 Superfortress.

BACK

TO TOP

|

|